Wage stagnation & Spain's low-bar 1%

The country of "opositores", over-qualified workers, and the two Spains.

Nobody comes to Spain to become wealthy - except foreign footballers and American investment firms.

Today there’s a feeling among Spaniards that Spain is only affordable for people who don’t have to live on Spanish salaries.

Rents are 24% above pre-2008 bubble levels. Property prices have increased 11 years straight - in 2024 alone they jumped 8.4%. New car prices are up nearly 40% since 2019.

Salaries, however, have barely budged.

The below chart created by economist Pablo García Guzmán shows how, since 1995, the average annual wage of employees in Spain has increased in real terms by just 3% (6% on a full-time-equivalent basis).

Low wages are a by-product of low productivity.

A CaixaBank report, The great challenge of the Spanish economy: to improve productivity, explains the root cause:

“In Spain, large corporations account for a smaller proportion of all companies compared to major advanced economies. Larger companies are generally more productive than smaller ones. This is partly because the most successful companies, which tend to be the most productive ones, grow the most. But larger companies also tend to be more productive because they have critical mass for certain investments and are in a better position to get the most out of them.”

“There is a Spanish mittelstand of mid-sized, often family-owned, manufacturers , especially in Catalonia, the Basque Country, Navarre, north-east Castile and Valencia,” wrote Michael Reid in Spain: The Trials and Triumphs of a Modern European Country. “And there there is the vast mass of low-productivity small and micro businesses. Under 1% of Spanish firms have more than fifty workers compared with 3% in Germany and 1.8% in Britain.”

With its Leprechaun economics, Ireland - a far smaller country than Spain - is home to the EMEA headquarters of tech giants like Google, Meta, Apple, TikTok, significantly boosting national productivity and average real wages (see chart above), especially in high-value-added services and technology sectors.

Today in Spain, a €90,000 gross salary puts you in the top 1% of earners.

In contrast, breaking into the top 1% requires salaries in excess of €300,000 in Ireland and €680,000 in the United States.

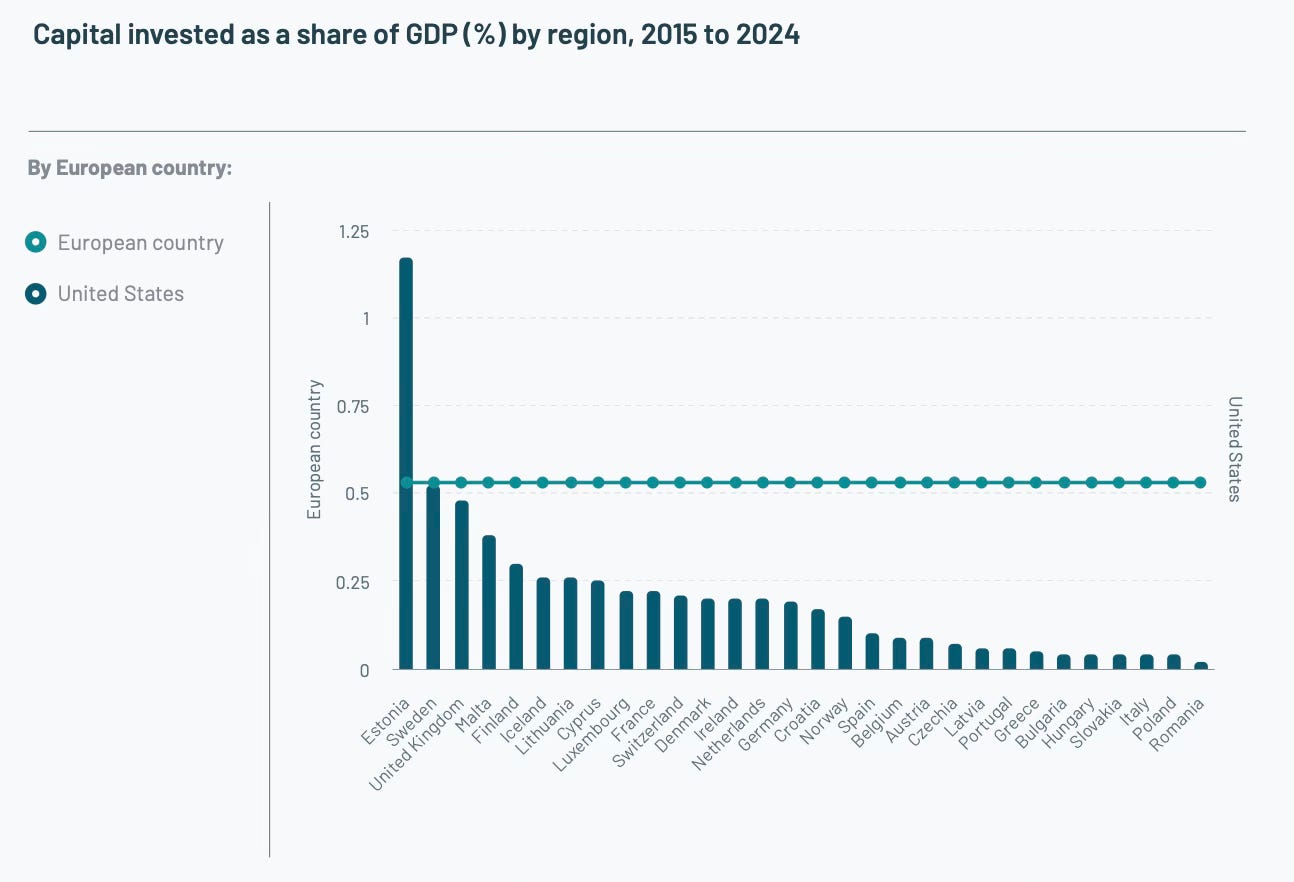

According to the State of European Tech Report 2024, 17 of the top 30 countries for tech investment are in Europe - Spain ranks 34th.

Instead of investing in the stock market, Spaniards buy property to let. In a country where renting apartments promises steady returns, why gamble on startups?

Wage stagnation

The low-bar 1% isn’t the real problem - the real concern is how low wages are for the majority of workers in Spain: 67% earn less than €30,000.

According to latest figures, the average annual gross salary in Spain is €23,350 - about 20% less than the EU average.

During my recent interview with James Blick, we spoke about the disconnect between Spain’s strong economic performance on paper and people’s day-to-day lives. Spain may be making headlines in The Economist for being the best performing rich economy, but people aren’t feeling it in their pockets.

In a report for El País, Kiko Llaneras explained how the income landscape has evolved in recent years:

“Between 2014 and 2024, Spanish household incomes rose by 20% in real terms. But there’s a catch: that improvement came thanks to unemployment being cut in half, not because of wage increases. In fact, salaries have barely grown in real terms and remain below the levels seen during the 2008 bubble. Since 2020, nominal wages have risen by 11%, but inflation has been 15% so purchasing power has been lost.”

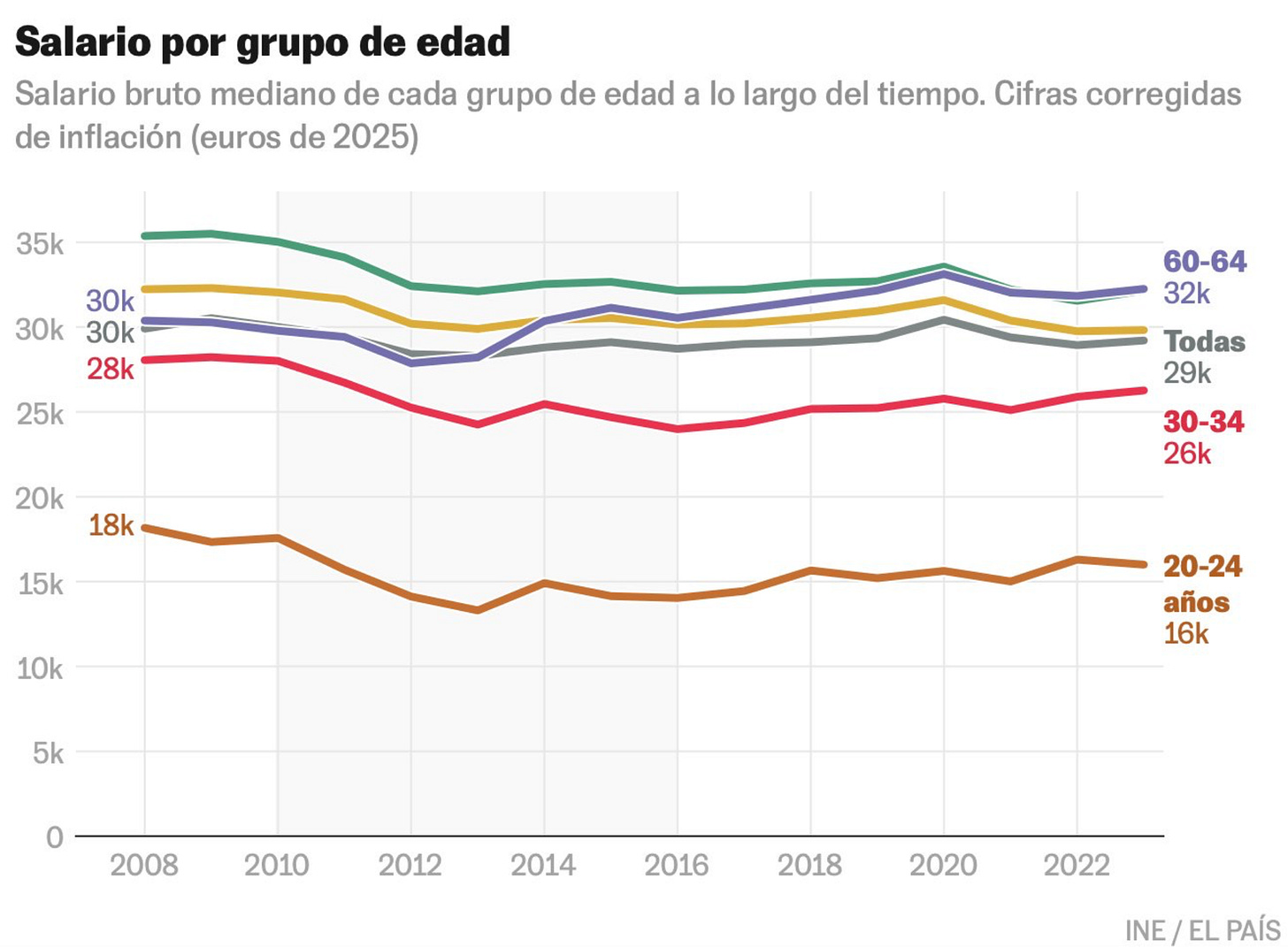

In his research, Llaneras found that only workers aged 60 to 64 earn more today than their counterparts did in 2008. Their median salary rose from €30,000 to €32,000.

All other age groups in Spain are earning less than people of the same age were 17 years ago.

This stagnation in wages and erosion of purchasing power helps explain a deeper, more persistent issue affecting millions across the country.

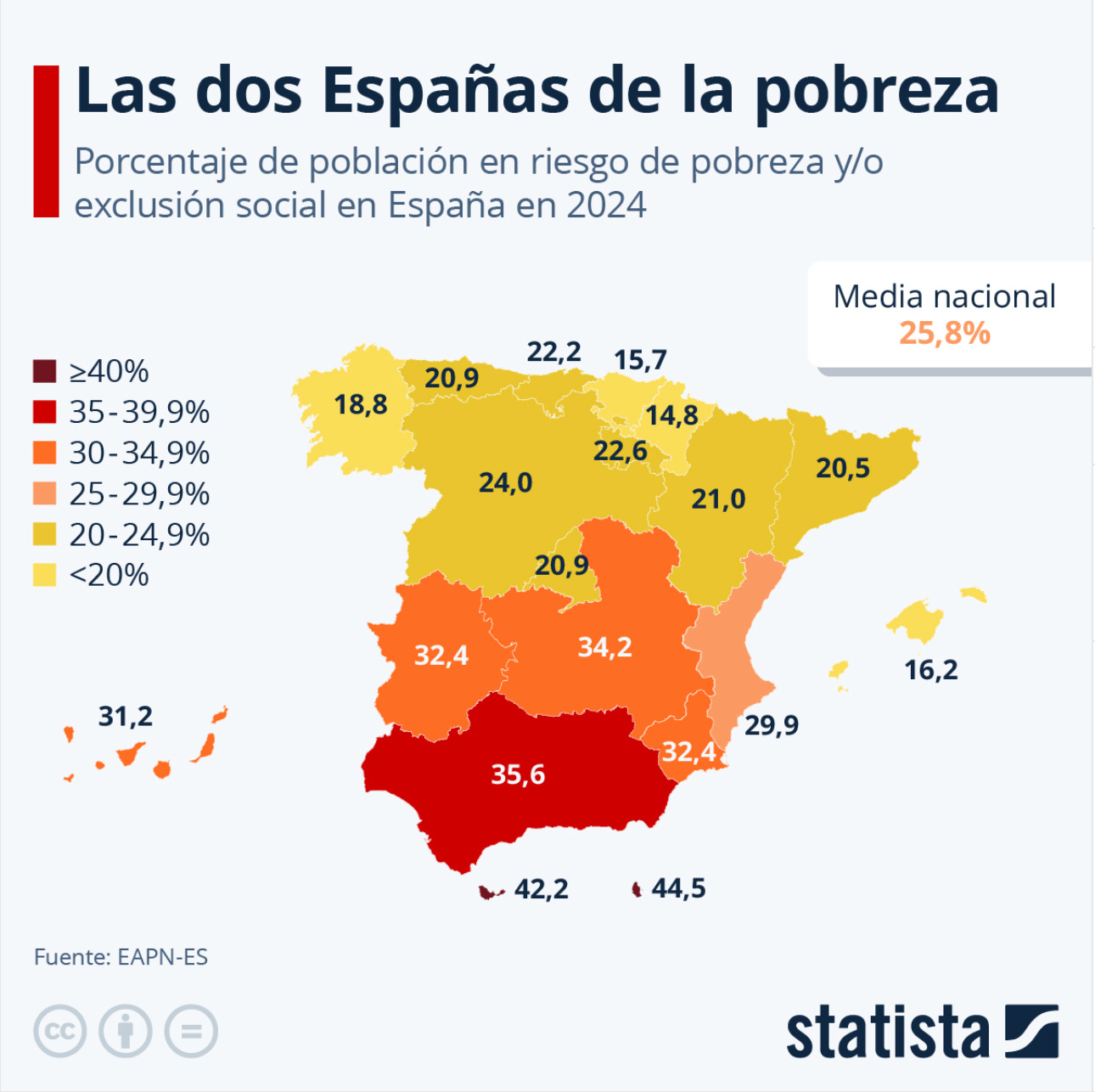

According to the latest AROPE “El Estado de la Pobreza” report, nearly 26% of Spain’s population - over 12.5 million people - was at risk of poverty or social exclusion in 2024. The report also highlighted the stark regional disparities, with 14.8% in the Basque Country compared to 35.6% in Andalusia.

This map shows the two Spains: the haves and have-nots.

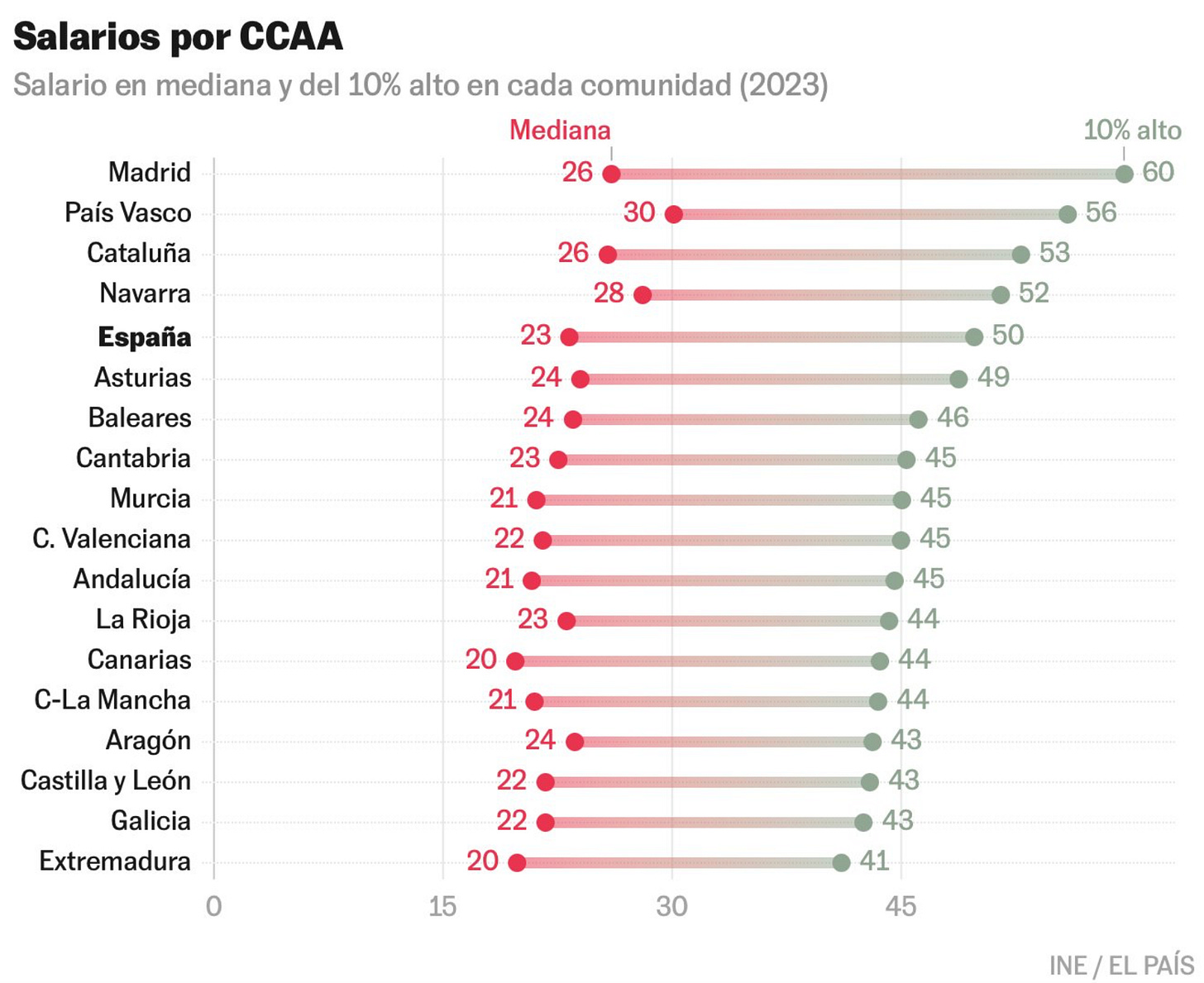

The Basque Country is one the haves.

It has the highest median salary (€30,000) - 50% more than in regions like Castilla-La Mancha and Andalusia. Madrid, meanwhile, stands out for its concentration of high earners. To be in the top 10% of income in the capital, you need to earn €60,000 a year - compared to €53,000 in Catalonia.

Take what you can get

Almost 36% of workers in Spain are overqualified for their jobs - the highest rate in Europe.

This mismatch between talent and opportunity reflects a deeper dysfunction in the labor market, where workers are forced to accept roles well below their skill level just to make it to the end of the month.

Contracts are precarious, wages low, and job security scarce - sustaining the “take what you can get” mindset.

What's more, piles of pointless red tape make it difficult to start a business - and then there’s the reality of being a small business owner in Spain.

A friend of mine who owns a clothes shop here in Galicia told me that she pays close to €400 just to be self-employed, an autónoma, every single month. If she doesn’t make a single euro in sales, the cuota still has to be paid. An Italian friend of hers who is also an autónoma continues to be baffled at a system that discourages entrepreneurship: “Can someone please tell me why I have to pay to work?”

It’s a system that punishes risk and initiative - no wonder so many Spaniards are seeking the stability of government employment. Today, there are over 3 million state workers in Spain, an increase of around 400,000 over the past decade.

In early 2025, there were 239,600 more public employees than self-employed workers in Spain - a stark indicator of a country drifting away from entrepreneurship, innovation, and economic dynamism. To compound matters, 40% of adults aged 18 to 24 today are planning to opositar, to sit one of the official public sector exams.

“More and more young people aspire to become civil servants not out of a sense of public service, but because the private sector offers no viable prospects,” said economist Marc Vidal.

According to El Mundo, the average salary in the public sector is 45% higher than the private sector. Beyond the financial incentives, public sector jobs are appealing for their more family-friendly working hours, which allow people to conciliar - enjoy a healthier work-life balance than many private sector roles can offer.

Aspiring civil servants often spend years studying, either reducing their working hours or leaving their jobs entirely to prepare. This is bad for the economy.

Many of these candidates are highly qualified professionals willing to take on jobs well below their capabilities in exchange for long-term stability. This drains talent from the private sector, weakening its ability to grow, innovate, and raise wages - the very things Spain’s economy needs most.

A recent El País podcast episode - Spain, a country of opositores (people preparing for public exams) - highlighted another growing concern: 40% of civil servants in Spain are now over the age of 50.

While public sector employment (16.55% of total employment) is below the OECD average of 18.6% , the trend is still significant and increasingly skewed by an aging workforce. Over the next 10 to 15 years, waves of retirements will open up a large number of public sector jobs, luring even more young workers to pursue civil service careers.

Spain used its talented civil service to carry out impressive national projects, such as building a high-quality universal healthcare system and developing one of the most advanced high-speed rail networks in the world. Now the challenge is getting the next generation of top talent into the private sector instead of safe government jobs.

“The story for Spain is very good in terms of headline numbers, but in the medium term we need the private sector to regenerate itself,” said Joe Haslam, professor at Madrid’s IE University on The David McWilliams Podcast. “We need the best people and (more) great companies like Mango and Inditex (Zara), and I don’t see a lot of those on the horizon. This is eventually going to be a problem.”

Without a dynamic private sector, Spain risks over-reliance on the state - the last thing it can afford is for entrepreneurship to fall further out of fashion.

Until next time amigos,

Brendan

***You can support the research, translation, writing, editing, and newspaper subscriptions behind this content with a one-time contribution - gracias!***

See also: Spain’s plan to keep young(er) adults forever young: The housing crisis, postponed adulthood, Tom Hanks, and a system that redistributes from the haves to the haves. Read now

Great summary of Spain's low wages, disencouraging autónomo system and the maze of red tape!!

Excellent stuff. Reform of the hated and counterproductive autonomo system is a leap of faith no one seems willing to make. It’s baffling, a nation of trapped talent.