Spain's turn to listen and learn

The 50th anniversary of Portugal's return to democracy reminds Spain that a transition isn’t a revolution.

For one day at least, all eyes were on Portugal.

Then Spain happened. Again.

A discrete country left alone to face the Atlantic and contemplate its continental solitude, not much happens in Portugal. Nothing click-baity enough to wrestle media attention away from the other side of the Iberian divide anyway.

April 25th, 2024, alas, was supposed to be Portugal’s day, a moment for Europe to salute the 50th anniversary of the peaceful Carnation Revolution that toppled the longest dictatorship in Europe.

And besides, in 2025, Spain would have its own moment to “celebrate” five decades of post-Franco freedom. Pedro Sanchez, however, decided that this was the perfect day to consider resigning as prime minister, pointing to how viciously personal Spanish politics has become and the threat that misinformation poses to the country’s democracy. He gave himself five days to decide whether “all this was worth it.”

Sanchez’s announcement lurched Spain back into its business-as-usual political disarray. Ticking clocks counting down to the Monday morning decision sprung up on the screens of news programs where long tables of tertulianos clashed as Sanchez asked himself, Should I stay or should I go?

While it was all very ceremonial and politely emotive on the streets of Lisbon with red flowers (carnations) and tanks that looked more like life-sized toys, Spain was, for five delirious days, even more Spain.

This was the Iberian Peninsula perfectly on brand.

An insular peninsula?

When asked to define how Spaniards view their Iberian neighbours, I can only answer in the most Galician of ways: Depende.

Due to geographical and, in turn, historical and cultural factors, Galicia generally enjoys a close relationship with Portugal. “A third motorway connects Galicia with Porto, in northern Portugal, in what has become a seamless economic region,” wrote Michael Reid in Spain: The Trials & Triumphs of a Modern European Country.

Friends of mine here in Galicia drive across the border for weekend breaks several times a year. They praise the quality of locally-produced Portuguese goods such as ceramics and clothing.

TVG has a full-time correspondent based in Portugal, and it’s not uncommon for news stories (broadcast in Gallego, Galicia’s official language) from Lisbon to feature ahead of Madrid and Catalonia in the running order. Language similarities mean that Portuguese interviewees on Galician TV are rarely subtitled. What’s more, Porto - just over a 90-minute drive from Vigo - is Galicia’s international airport of stature in all but name. Many on the other side of the border come to Galicia to fill their tanks with cheaper petrol and their trunks, I imagine, with the nicer beer.

Galicia is a region whose indentity is inextricably linked to emigration and the notion of morriña - the longing for a land, a person, the past. With its own version of morriña (saudade), Portugal shares this morbid, romantic, and fatalistic kind of melancholy and nostalgia that is personified by the music that tourists in Lisbon enjoy every evening: fado, a word that derives from the latin word fatum (fate).

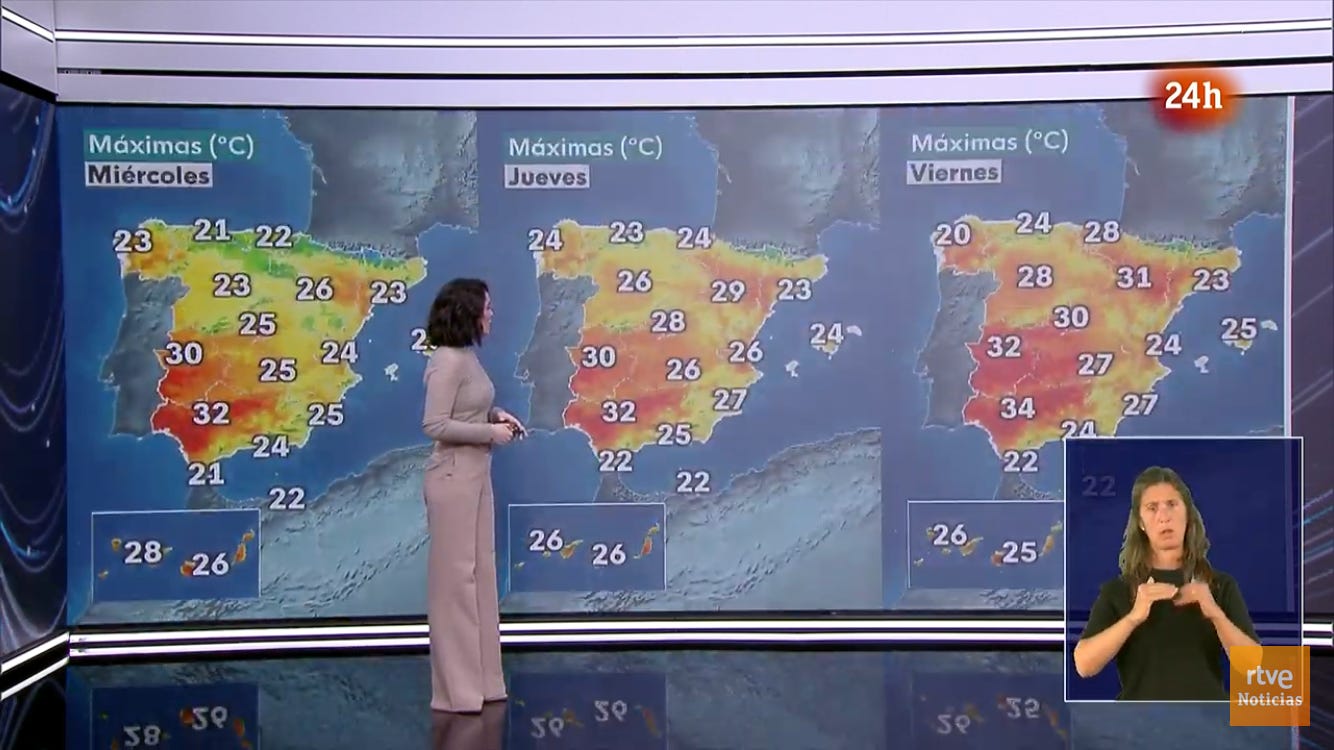

Portugal’s relationship with the rest of Spain, however, isn’t quite as fraternal. Or maybe it is. There are, of course, big brothers who act like their sibling doesn’t exist. A friend once joked that Spain’s weather map, which completely ignores Portugal, is the image some Spaniards have of the Iberian Peninsula.

There are others, meanwhile, who believe that the time difference between the two countries is far greater than 60 minutes. A man I got to know in the first bar I called my local in Madrid once informed me that “Portugal is Spain of the 1970s.”

When I put this quote to Galicians, they've been quick to tell me that many Madrileños also view the people of this lush green corner of Spain as being backward and uncultured.

Nonetheless, the Pedro Sanchez soap opera aside, I got the feeling that there was a genuine interest and admiration among Spaniards towards La Revolución de los Clavales. Across the national and local media, there were numerous feature pieces, documentaries, and podcasts.

Spain had, for a few days at least, turned around to face its neighbour.

“The reports, interviews, and stories around the 50th anniversary of the Carnation Revolution not only make it easier for new generations of Spaniards to understand the recent history of Portugal and how it showed the way for Spain’s Transición,” wrote Jorge Fauró, “but they also also make us realise the unjustified superiority with which we have treated our neighbouring country.”

In Ireland, this is something we are familiar with.

The PIIGS

“There is no doubt that Ireland’s economic performance in the late 1990s was genuinely remarkable. The number of people at work doubled, from just over a million in 1988 to 2.1 million in 2007. The population rose at a phenomeal rate. While the rest of the EU added one person to every 1,000 between 1998 and 2008, Ireland added ten. All of this was wonderful to live through, and it was also a lot of fun.”

We Don’t Know Ourselves, Fintan O Toole.

As a 1988 baby, I was part of the first generation to grow up in an Ireland that was prosperous and self-sufficient. Unlike my aunt Sarah in London or cousin Liam in Boston, I wouldn’t have to take a plane or “the” boat to make it.

From Tralee, a southwest working-class town, I never looked at the English or Americans on TV and felt inferior. Why would I? Life was good and comfortable and peaceful. Family holidays abroad became more frequent. There was no yearning to make it anywhere else than Ireland.

My generation developed towards adulthood inside a bombastic Celtic Tiger bubble that would burst spectacularly in 2008. An asphixitating banking crisis bundled Ireland together with Portugal, Italy, Greece, and Spain. We were The PIIGS. The planes and boats beckoned again.

Today, 20 years later, in Spain, I’m still trying to figure out what making it means.

A nostalgia junkie from a nostalgic nation, I offer little resistance when the YouTube algorithm direct clips from Ireland’s greatest TV series my way.

“How did a repeat of a repeat of a repeat of a repeat become one of most watched programmes on Irish television in 2020?” asked Laura Slattery in The Irish Times. Set to an impeccable soundtrack, each episode of Reeling in the Years recaps of the events that shaped domestic and international life during a given year.

Distracted down a YouTube rabbit hole while I was supposed to be researching for this piece, I noticed a lot of Ireland in the Portugese DNA:

The geographic isolation.

Generations of people kept down through fear and under-education.

A history of emigration tied to economic hardship.

The inherited shame and feeling of being Europe’s down and outs.

A lack of self-confidence due to an opressed life under colonial rule and later the Catholic chuch (Ireland) and a fascist-light dictatorship (Portugal).

Life in the shadow of a threatening neighbour.

“Now, on to Portugal!” was the cry in Madrid among a strong part of the Spanish Falange, the extreme nationalist political group, after the Civil War had been won. Franco needed little encouragement. He had, after all, already written a dissertation whose title wouldn't look out of place in a weekend travel supplement for mass tourism: “How to invade and conquer Portugal in 72 hours.”

Any invasion would have needed the help of Hitler, with whom Franco met on October 23rd, 1940, in Hendaye, a French town on the Basque Coast. But the Germans would eventually dive head-first into Operation Barbarossa before being dragged into the Russian winter. Operación Felix remained on the shelf.

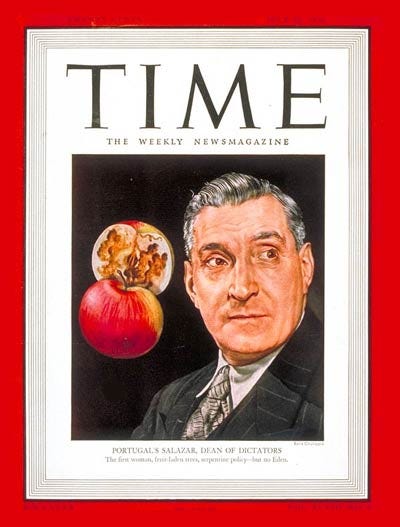

With Antonio Salazar already in power, Portugal didn’t need to be invaded by a dictator to know what life under one was like. Dominic Sandbrook of The Rest is History Podcast described Salazar as being very reactionary, ultra catholic, and anti-modernity, a man who “wanted to stop the clock.” A former professor of economics at Coimbra University, the unmarried Salazar was viewed as being academic and frugal and a ferocious worker who goverened like a professor. Time magazine referred to him as “the dean of Europe’s dictators.” In winter, he refused to turn on the heating because it was deemed a waste, opting instead to work with his coat on.

While he helped restore stability to an economy crippled by inflation, Salazar turned Portugal into a hermit, inward-looking state that was “proudly alone.”

Staying true to Portuguese understatedness, Sandbrook explains how Salazar “holds no rallies, there’s no personality cult…he has no interest in mobilising the masses, he doesn’t really sell himself as anything other than a cathlolic technocrat to the public. There was no sense of energising people or military expansion…You cannot picture him on a balcony addressing great crowds.”

He goes on to compare Salazar to the neighbouring dictator: “Franco is a very unlikeable man. He’s a great show-off. He’s all about lots of medals, lots of pomp. His family become incredibly rich.” In contrast to Franco, Mussolini, and Hitler, Salazar's de-personalised regime was fascist-light.

As Spain finally began to open itself to the world by embracing bikinis and Speedos, it quickly became evident after the Carnation Revolution how far Portugal had been left behind. More than one-third of the population was working in the primary sector. In 1970, 22% of men and 35% of women older than 15 were unabe to read. What’s more, Portugal was the last country in Europe to de-colonise after a series of costly colonial wars that drained some 40% of the country’s annual budgets. A once mighty colonial force quickly became a frail and frightened failed state.

In 2023, Spain’s population had increased by more than 14 million since 1975. Portugal’s population, on the other hand, only rose by just over one million.

The decades of economic hardship that followed still condition the national psyche today. “Among all the feelings that float around inside a Portuguese person,” explained the Portuguese writer Gabriel Maglhães in El país que nunca existió (the country that never existed), “there is one that stands out: insecurity. A constant doubt about onself and his country. Maybe this explains why us Portuguese have a discreet presence, as if in our own shadow, and why we usually speak in a quieter tone than the Spanish shouting you hear in bars.”

Portugal’s post-colonial identity crisis is best reflected in the title of José Gil’s famous book: O medo de existir (the fear of existing).

According to Maglhães, a sure-fire way to offend a Portuguese person is to throw the country’s economic struggles in their face. “Then you might see a person who usually speaks quietly begin to raise his voice.”

He also explains how the Portuguese are wired to eliminate economic difficulties from their consciousness. “Maybe this is where our ability to disguise as wealth that which is modesty comes from, like covering a small house in beautiful ceramic tiles in order to forget about its size. This type of make-up is applied to everything in Portugal.”

But for all its insecurities, Portugal emerged from the initial political turmoil and uncertainty that ensued during the aftermath of the Carnation Revolution to become a stable, functioning democracy, and an important member of the European Union.

Lisbon and Porto are popular among Spaniards - Gallegos and Madrileños alike - for cheap (nowadays not so cheap) getaways during Semana Santa or other puentes. But instead of seeking out cinnamon-sprinkled pasteis de nata and cholesterol-spiking francesinhas, Spain - and its mediocre political class in particular - should instead look to listen and learn from its quiet and quietly-efficient Portuguese neighbours about how to live with the sound down and, more importantly, how to properly put a dictatorship to bed.

Learning lessons from Lisbon

If Portugal uses majestic ceramic to conceil its economic modesty, Spain uses nauseating noise and media-driven hysteria to avoid addressing, once and for all, its deep political failings.

“One has to ask why there’s such an abysmal difference between the behaviour of Spaniards and Portuguese,” wrote José Manuel Ponte en La Opinión. “In Portuguese cafes and restaurants people speak quietly, rather than the screaming we have here.”

I’ve called Spain “home” since 2016, but it still takes me approximately 5.5 seconds to decipher whether the people shouting on the street are saluting or berating one another.

Life is loud.

“Noise, in Madrid, in Spain as a whole, is just background,” wrote Giles Tremlett in Ghosts of Spain. “It is part of the atmosphere, like air or daylight.”

Despite the shouting of orders and the shuddering clatter of cups and cutlery, I still get the impression that there are more deals done over a café con leche or menú del día than in the Spanish parliament. People may shout in the bar, but at least they listen - the same cannot be said for the country’s MPs.

For many, Las Cortes Generales is an arena for settling scores and hurling personal insults rather than furthering the interests of the people they are paid to represent. Spanish taxpayers are getting a bad bang for their buck with its current political class.

To collectively mark half a century of democracy, Portugal and Spain have organised official gatherings for the coming months. “A shared celebration, however, shouldn’t make us think that a transition (Spain) is the same as a revolution (Portugal),” wrote David Martín Marcos, a professor of modern history, in El País. Pointing to the ousting of Salazar’s successor Marcelo Caetano on April 24th, 1974 (he fled to Brazil), he explains how it was “nothing like the natural death of the dictator Francisco Franco on November 20, 1975 and the state funeral that followed.”

While all traces of Salazarismo were wiped clean from Portuguese institutions, the vision of a post-Franco Spain transición was imagined and implemented from what Martín Marcos termed “the heart of an authoritarian regime that progressively went about dismantling itself before eventually carrying out a controlled implosion.” There was no clean break from the past, nor a clean slate for the future. Spain is still stuck somehwere in between.

“How many other European nations entered the twenty-first century with ministers from a right-wing dictatorship still active, and powerful, in politics?” wrote Giles Tremlett in reference to Manuel Fraga, minister of information and tourism during the Franco regime and the founder of Spain’s conservative party, Partido Popular (PP).

I don’t expect any grand ceremony in Madrid for next year’s 50th anniversary. Spain - and the brash element of the conservative right in particular - will likely be more Portuguese than the Portuguese themselves for a few days at least.

Because the country pacted to olivdar, forget, rather than put in place the necessary mechanisms to process its bloody past, stop-gap solutions are still just stopping gaps.

Spain has moved on dramatically since 1975, but its 1978 constitution has stood still. “If a country like Portugal, with one dominant language and cultural uniformity has needed five profound constitutional amendments,” wrote Gabriel Maglhães, “how can it be explained that Spain hasn’t even had one constitutional change of any real magnitude?”

To further underline this unfit-for-purposenss, Maglhães also cites the example of the United States constitution which had, at the time of writing, registered 27 amendments in 233 years. There have been two small amendments to Spain’s constitution - both mandated by the EU.

Spain’s constitution has been stuck in time because, all too often, its leaders see nothing wrong with wasting time point-scoring down in the mud, shouting about ETA and bullfighting, turning the political debate into a repeat of a repeat of a repeat of Reeling in the Years.

“The emergence of a multi-party system might have been expcected to blunt crispación (tension), and promote cooperation,” wrote Michael Reid in Spain: The Trials & Triumphs of a Modern European Country. “But it has done the opposite. There are now two multi-party blocks where there were two parties.” He argues that the new centrifugal political dynamic gives the PSOE and PP little incentive to take conciliatory stances.

Luis Ángel Sanz of El Mundo tells me that, in Madrid, there’s a certain “healthy envy” towards Lisbon and the ability of its politicians to do their job: “Portuguese politics today is less crispada and confrontational, and more productive.” He also uses a word that keeps surfacing when people here talk about their Iberian neighbours: sosegado. Calm, peaceful.

![boats docked near seaside promenade] boats docked near seaside promenade]](https://images.unsplash.com/photo-1555881400-74d7acaacd8b?crop=entropy&cs=tinysrgb&fit=max&fm=jpg&ixid=M3wzMDAzMzh8MHwxfHNlYXJjaHwyfHxwb3J0dWdhbHxlbnwwfHx8fDE3MTUyODczMzd8MA&ixlib=rb-4.0.3&q=80&w=1080)

In the current quantity-trumps-quality media landscape, the rise of the far-right is good for business. With the emergence and electoral success of Chega, Portugal was suddenly interesting. But the fact that the Socialist party (PS) agreed to support the centre-right Democratic Alliance (AD) in the formation of a minority government, thus keeping Chega out, barely got a mention. Political cooperation, it seems, doesn’t quite get the juices, or the clicks, going.

Youth unemployment in Portugal is high (18.6% in 2023), but it has more than halved since 2013. Wages are considerably lower than Spain (minimum wages are €820 v €1,134), but the resourceful Portuguese have proven themselves adept at stretching their resources. “Spain would do well to look at Portugal,” wrote Michael Reid, “which produces better educational outcomes with less money.”

The Portuguese have an early leg-up when it comes to learning English because foreign TV isn’t dubbed. There are Spaniards who watch Jason Statham movies every second Sunday afternoon and have no idea what his real voice sounds like.

“In general, Portugal is more open to linguistic coexistence (than Spain),” wrote Gabriel Maglhães, “not only on a peninsular level, but also globally. Curiously, the Salazar dictatorship didn't close itself in on its language, as was the way with Franco. Us Portuguese have a strong notion of our fragility and one of the ways to survive and get ahead consists of moving the best we can between different languages.”

Despite being able to understand Spanish much easier than Spaniards understand Portuguese, and the geographic proximity, Madrid has never been the promised land for Portugal’s emigrants. Instead of paying attention to its west, “Spain has traditionally looked north of the Pyrenees,” Tereixa Constenla, the Portugal correspondent for El País, tells me, “but Portugal has also looked more to London and Paris than to Madrid.” According to the Financial Times, some 106,000 Portuguese citizens live in Spain compared to 1.2 million in France.

In Impossible City: Paris in the Twenty-First Century, Simon Kuper mentions a fellow neighbourhood football dad, Tomás, who “over time has grown confident enough to advertise rather than hide his Portugueseness.” No longer proudly alone, this year more than most, Portugal is just proud.

Maglhães argues that the country's openness and spirit of “linguistic tolerance,” something that’s drilled into people from a young age, is one of the key reasons why many Portuguese political leaders such as António Guterres and José Manuel Barroso have held high-level positions on the international stage.

“I prefer Portugal’s calm way of doing politics,” wrote José Manuel Ponte. “Spain’s way is entertaining, but in the long run it’s unbearable.”

Here's hoping the Carnation Revolution celebrations inspire Spain's politicians to park nonsensical rows, turn down the sound, and get to work.

Obrigado Daniela!

At some time in the mid-1970s, packed in the back of a Renault 4 and with us kids enjoying all the fun of short shorts on hot vinyl seats, my family went on a continental holiday,

- leaving an Ireland where the jingling ass-and-cart was still how farmers in Galway and Clare brought their milk to the creamery;

- driving through a Spain where, in her isolated farmstead somewhere in the drab, sun-cursed plains of La Mancha, a woman on a wooden horse-drawn sled turned in endless circles to thresh wheat;

- to a Portugal where bullocks pulled the brightly-painted wooden fishing boats of Nazaré off the beach into the crashing waves of the Atlantic.

It's all gone now, and - as far as living standards and harsh working lives go - good riddance. But it makes me feel like a time traveller to have seen all this in the flesh. 😀