Is the Mediterranean diet dying?

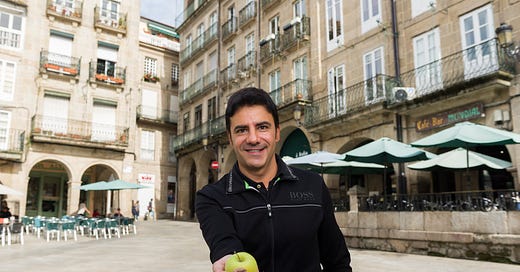

Pablo García Vivanco on Spain’s changing food culture and the health lessons to be learned from the "Galician Okinawa."

By the time Juan Carlos I took the throne in November 1975, restoring the monarchy after the dictatorship, a very different kind of king had already rolled into Madrid.

Fifty years ago this week, the first Burger King in Europe opened its doors in Plaza de los Cubos, just off Madrid’s Plaza de España.

That also makes the fast-food chain three years older than Spain’s 1978 constitution.

However, in a country renowned for long lunches and dinners that stretch long into sweltering summer nights, the idea of grab-and-go feels at odds with the image of Spanish food.

We think of jamón and tortilla, sun-swollen tomatoes and sardine skewers sizzling by the beach in Málaga or Cádiz.

In recent years, media outlets have lauded the Mediterranean diet as a key reason behind the longevity of Spaniards.

Yet today - 50 years later - the Madrid region is home to 200 Burger King restaurants - 100 alone in the capital.

Spain finds itself caught in a growing tension between past and present: time-honoured, healthy eating rooted in seasonal, local produce, versus the on-demand convenience of ultra-processed food and a dwindling resource: time.

According to a CIS survey, 69% of respondents who said they cook at home less than ever attributed the trend to a fast-paced lifestyle that leaves little time for meal preparation.

This week I sat down with Pablo García Vivanco, a dietitian-nutritionist and president of Ourensividad, a not-for-profit dedicated to studying longevity in the “Galician Okinawa” to find out whether the Mediterranean diet is dying.

So here is my interview with Pablo García Vivanco - enjoy!

The Mediterranean diet in 2025: Myth or reality?

Q: In his book about Spain, Michael Reid wrote: “The Mediterranean diet is now more myth than reality.” Do you agree?

A: In this book, Reid cites a prediction by the British historian Sir John Elliott who, in 2008, suggested that “the period between 1975 and 2000 may come to be seen in retrospect as a second golden age of Spanish history.”

I’d say our food habits reflect this notion.

Between 2000-2008, immigration boosted Spain’s population from 40 to 45 million, introducing new cultural influences and fuelling demand for convenience foods. This period also saw a sharp rise in the availability and consumption of ultra-processed foods (UPFs), which has contributed to a growing burden of chronic disease - and, in response, renewed interest in traditional dietary models like the Mediterranean diet.

That said, here in Galicia - where we follow what’s known as the Southern European Atlantic Diet - the picture looks different. According to Spain’s Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Galicia leads the country in fresh food consumption and ranks last in processed food intake, which is quite remarkable.

This suggests that our Atlantic dietary culture has been less affected by global fast-food norms than the Mediterranean one. While both diets are nutritional powerhouses, they haven’t proven equally resilient to change.

The true cost of convenience

Q: The rise of ultra-processed foods is a global story. Have you seen that trend take hold in Spain in recent years? And if so, what’s been driving it?

A: Several studies now link processed meats — though not unprocessed red meat — with shorter life expectancy and age-related diseases. Unfortunately, Spain hasn’t escaped this trend.

Major global food chains have become entrenched across the country, and their growth is tied to time scarcity, changing family priorities, and — crucially — aggressive marketing.

A study from the University of São Paulo, published by National Geographic, found that 20.3% of all food consumed in Spain is ultra-processed. That puts us second in the Mediterranean region, after Malta.

It’s a deeply concerning figure.

A(nother) generational divide in Spain

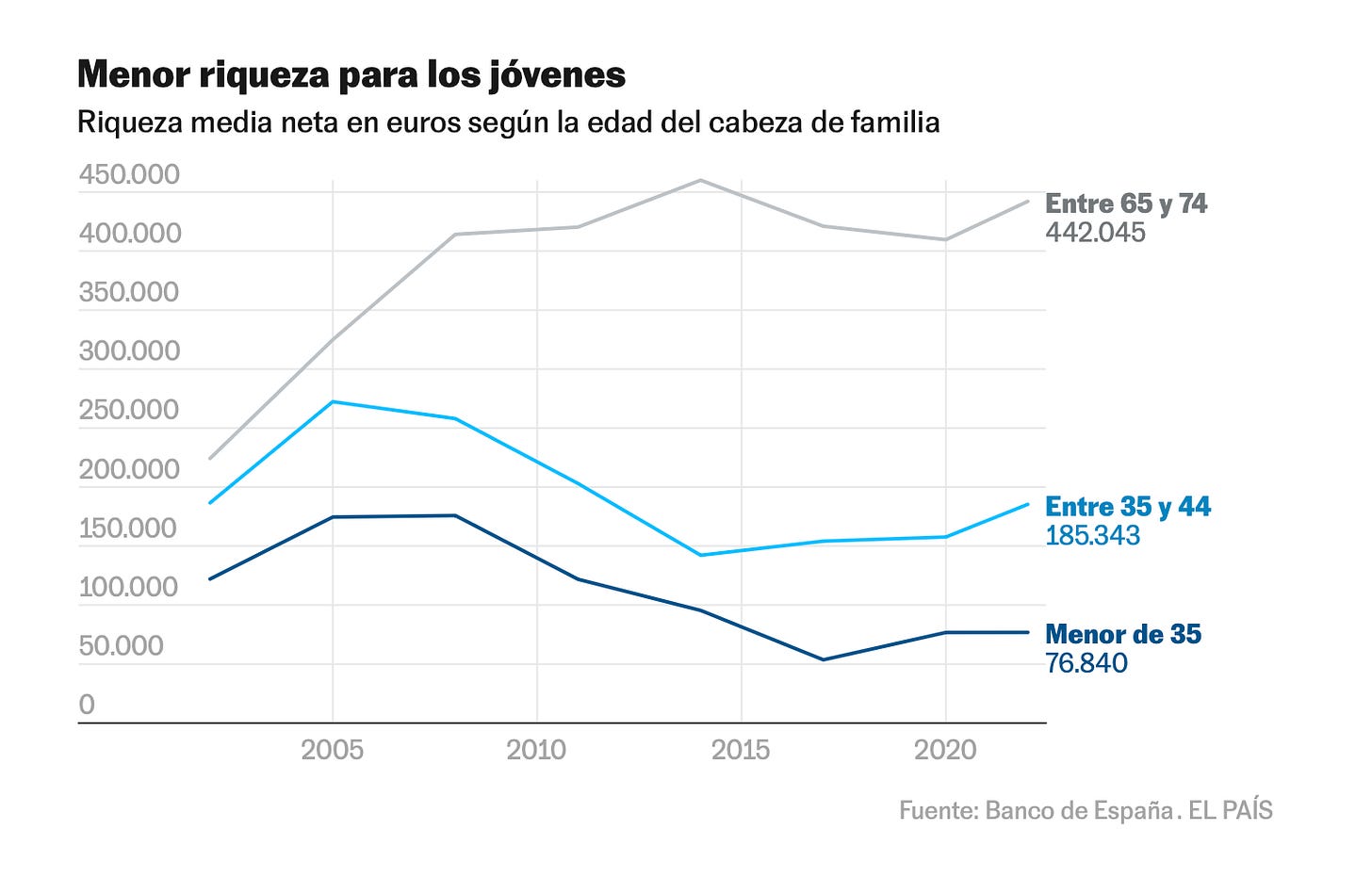

Q: There’s a stark generational wealth gap in Spain. Many young adults face the grim reality that they’ll never be able to buy a home because their stagnant salaries have been left in the dust by a property market on steroids. Do you see a generational divide in diet quality too?

A: Absolutely. Let me give you an example. We recently published a study on the dietary habits of people over 100 years old in the province of Ourense. Of the 115 centenarians we interviewed, not a single one consumed processed food. Every one of them had access to a personal or family vegetable garden.

This direct access to homegrown produce eliminates additives and preservatives - such as acrylamide, dioxins, nitrites, nitrates, and food dyes - many of which have been linked to cancer. The results were striking: 80% of these centenarians were taking four or fewer medications, a threshold below what’s considered 'polymedicated’ (taking an excessive number of drugs simultaneously).

This supports a broader conclusion: eating fresh, local food with minimal additives improves health and reduces the risk of chronic disease. Ultra-processed foods have been associated with obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and certain cancers — the four leading causes of death globally.

A U.S. study involving over 200,000 participants - along with a meta-analysis of 1.2 million individuals - found that high UPF intake was linked to a 17% higher risk of cardiovascular disease, a 23% higher risk of coronary heart disease, and a 9% higher risk of stroke. These aren't marginal effects.

Food inflation, chain reaction

Q: Since the Covid-19 pandemic, Spain has experienced steep food inflation - especially for healthy staples like olive oil, eggs, fruits and vegetables. Meanwhile, salaries have barely budged. What impact is this having on eating habits?

A: You mention olive oil - and rightly so. At one point, prices rose by 40%, and consumption dropped significantly. In 2024 alone, Spain saw a 7.5% decrease in olive oil consumption compared to the previous year, down to 264.7 million kilos.

It’s basic economics: prices go up, demand goes down. According to the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, and Food, Spaniards bought 11.7% less olive oil in 2024 as average prices rose 36.7% - far outpacing general food inflation at 20.8%.

All categories of olive oil were affected — extra virgin, standard olive — with volume declines of 12.2% and 13.7%, respectively.

Worrying health trends

Q: Life expectancy in Spain continues to grow but younger generations are eating worse. Between 1987-2020, the rate of obesity among adults in Spain increased by 115% . Moreover, its ageing population will further overload an already saturated healthcare system. Are there still reasons for optimism?

A: Life expectancy has been growing, and with the discovery of certain drugs, and will continue to do so. Artificial intelligence will also boost the world of healthcare. The in-depth study of our microbiota will also provide us with many answers, since this kilo and a half of bacteria performs important functions such as the creation of short-chain fatty acids, trophic functions, immune functions and, above all, metabolic functions, with the formation of neurotransmitters.

Stress and fast food alter this microbiota - that’s why certain chronic pathologies have also increased, including autoimmune diseases. But with new research and knowledge we will be able to act accordingly.

The many Spains

Q: Spain’s cultural diversity is one of the things I love most - all the languages, histories, and food traditions. Do you, as an expert, see meaningful dietary differences across regions?

A: Definitely - and it’s one of Spain’s great strengths. The country’s geography, climate, and cultural diversity have created rich, regionally distinct food systems. And in terms of overall quality, the north really stands out.

The Atlantic Ocean is full of photosynthetic microorganisms, which feed into a nutrient-rich trophic chain. Our cold, deep waters mean that blue fish here contain more omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. As a carbohydrate source, the north also favours potatoes - often boiled - which are lower in calories and higher in fibre, potassium, and water-soluble vitamins than pasta or rice, which are more common in the south.

The south may produce more olive oil, but here in Galicia we consume more of it. We also grow unique greens like turnip greens and tops and cabbage, all part of the brassica family. These vegetables are rich in glucosinolates, which become sulforaphane - a potent anticancer and anti-inflammatory compound - during cooking.

Culinary techniques differ too: the south uses more frying, which involves high temperatures and nutrient loss. Here in the north, we prefer boiling in water, which preserves more nutrients and produces a healthy broth.

It’s those small details, repeated over generations, that shape population health.

Conclusion

If Spain continues down the same path as other late-stage capitalist societies and submits further to ultra-processed foods, we already know what’s coming.

In a recent Plain English podcast, Derek Thompson laid out the sobering health legacy of the American diet:

“For many decades, the U.S. has had higher rates of obesity and chronic illness than similarly rich countries. It’s not just the poor among us. Rich Americans die from heart disease more than similarly rich Europeans. In fact, every income group, every ethnic group and education group that reaches the age of 50 here in America arrives at that stage of their life more heavy, more unhealthy, and at higher risk for serious heart disease or metabolic diseases, like diabetes. In fact, according to the NIH, Americans who [seem] to have won the genetic and socioeconomic and behavioural lotteries - these are Americans who don’t smoke, who are insured, college-educated, rich - are still in worse health than similar groups in comparison countries.”

Spain still has a choice - and some major advantages.

This country is home to some of the world’s finest fresh ingredients and a food culture shaped by wisdom, tradition, and connection to the land.

It has a generation of centenarians whose longevity offers living proof of what local, seasonal, unprocessed food can do for the human body.

Letting those lessons die with them would be a costly mistake - one paid for in health and time we cannot get back.

Until next time amigos,

Brendan

***You can support the research, translation, writing, editing, and newspaper subscriptions behind this content with a one-time contribution - gracias!***

You may also be interested in this: Inside Spain’s first blue zone: Netflix take note.

Interesting, but I feel not the whole story. We live in a small aldea in Lugo province. When we first came here 17 years ago all our neighbours worked the land. They lived lives of self sufficiency that involved physical hard work. They had a diet low in meat and fish, high in potatoes, bread and vegetables, yes, but they also had to put in the physical exercise to get it. Their children and grandchildren have had to leave to find work and have little interest in this hard frugal life and as our neighbours die their land is being used for tree plantations or pasture by large meat producers. The houses in the aldea are becoming full of weekenders from Lugo or Madrid. I feel it is a combination of diet, exercise and forced frugality that gives that generation its longevity

An interesting and thought provoking article.

Upon moving to Spain (from France but I've lived in the UK and US too), I was struck by how unhealthy Spanish eating schedules are. A cup of coffee upon waking up followed mid-morning by breakfast out, usually consisting of jamón, eggs, bread but no fruit or vegetable matter. Lunch between 2 and 4pm, although probably more representative of the Mediterranean diet and, in the old days at least, accompanied by wine and inevitably followed by a siesta.

After school, kids get a snack, la merienda, which in my (limited) experience consists exclusively of ultra processed food. How many adults continue with this snacking habit, especially with their evening vermu?

Finally dinner is eaten absurdly late (10pm) with little time to digest it before going to bed. True, dinner in Spain tends to be a light affair consisting of.... jamón, cheese and occasionally some vegetable matter.

To my mind the Spanish eating times are screwy which forces people to snack in between and often outside the home with low access to non UPFs. There's not enough time to digest the principle meals before lying down (siesta or bedtime). It's no wonder that their life expectancy is falling especially as fewer people are connected with the soil and producing their own food.

Personally, I think Italian eating habits are both healthier in what they eat and WHEN they eat. And there's more room for a wider variety of fruits and veg in the Italian diet.