Catalonia: Time of the signs

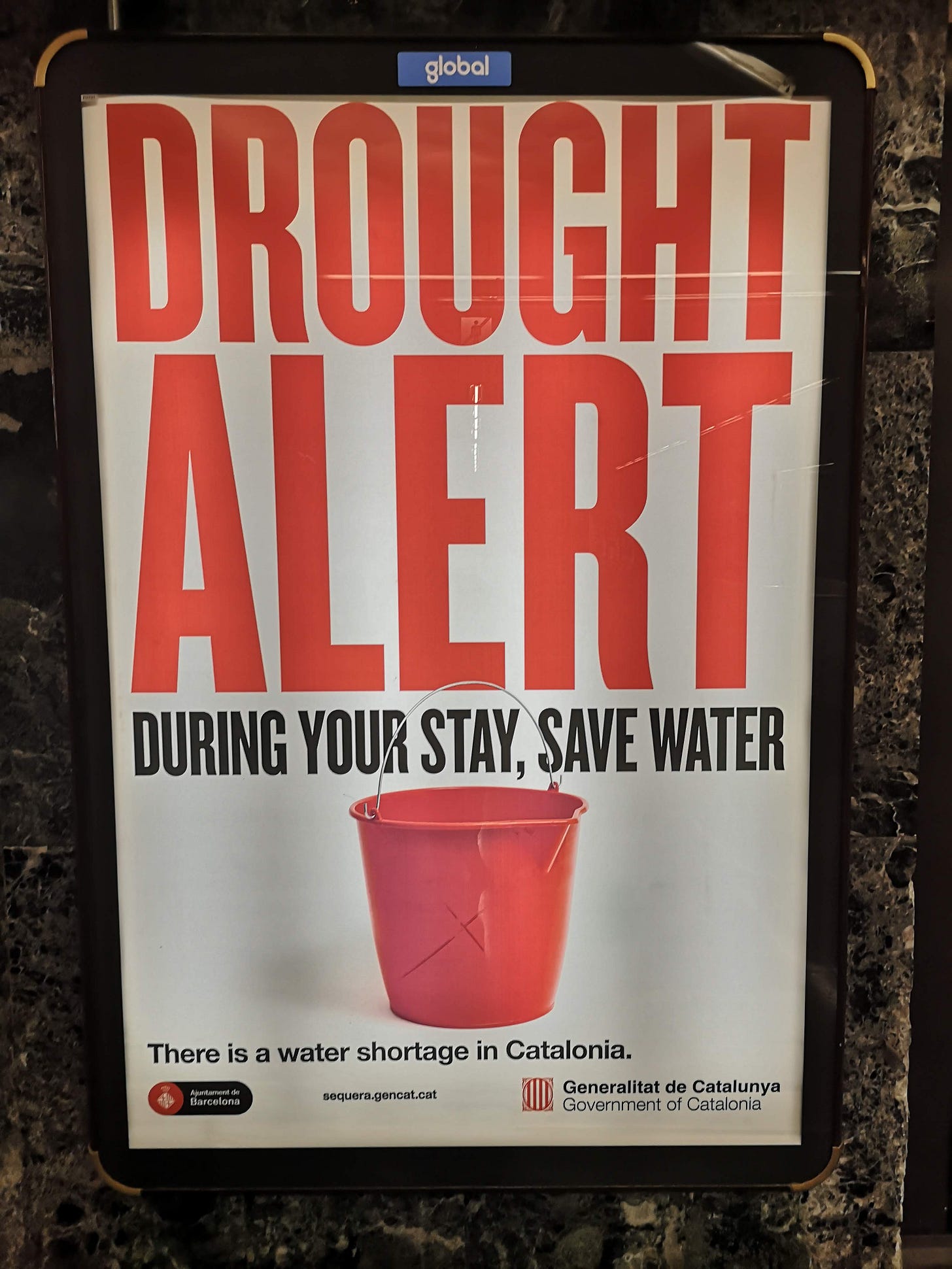

A dream destination for travellers across the globe, Barcelona and the wider Catalonia region are greeting visitors with a different list of buckets.

It’s not the kind of sign you expect - or want - to be greeted with upon landing.

Airport baggage claim areas and metro stops in Barcelona are prime advertising real estate, generally reserved for luring visitors into leaving more euros in the debit side of the local economy ledger: a rented car to explore the golden tones of the Catalan coast, a synchronized splash in an aquatic park, a tour of a football stadium where the best players in the world no longer play.

Most of the time, however, we’re too busy trying to detect signs of life from the baggage carousel or overhead screen to pay much attention to the same type of experience ads we’ve seen a thousand times elsewhere.

A big red bucket beneath “DROUGHT ALERT” in bold red letters, on the other hand - now that’s unignorable.